. Leaving Jurassic China behind, our excursion carries us northwest across Laurasia until we reach Europe. Early Jurassic England was connected with the rest of Europe, and these lands were coated in vast swathes of conifer forests. Roaming these forests was the thirty-foot-long and three-ton prosauropod

. These forests were also stalked by the medium-sized theropod predator

, which could grow up to ten feet in length and probably weighed 220 to 300 pounds. It may have hunted

and kin in the fern-covered valleys and muddy floodplains. As we venture farther west to the English seacoast, we look out to sea and see numerous islands rising from the shallow waters teeming with ichthyosaurs preparing to give birth to live young. In modern times this area is South Wales, but during the Hettangian it was a collection of shallow, forest-covered islands. The seven-foot-long theropod

prowled these islands, swimming the channels between them and hunting small vertebrates such as lizards.

As we island hop across the warm, shallow sea, we reach another coastline thick with conifer forests. Unbeknownst to us we just crossed the genesis of the North Sea and have reached North America, considered the northwestern portion of Laurasia. These forests were home to the thirteen-foot-long prosauropod

. It had a wide range: its remains have been found as far south as modern Africa, and it may have made some trackways recently discovered in Nova Scotia. As we head southwest, leaving the burgeoning Atlantic coastline and making our way into the interior of the modern United States, we may come across some

, successful survivors from the Triassic Period who would diversify and radiate throughout the Early Jurassic (some even show up in China).

, which grew to three feet in length and weighed close to ninety pounds. This terrestrial, carnivorous proto-croc had pillar-like legs and its body was covered by osteoderms in a double row along the back and more covering the bottom of its body and running the length of its tail. Its five toes were clawed, and it would’ve been both a good runner and a good swimmer. If we were to disembark our caravan and comb through the topsoil, we might come across

, an amphibian that shared many characteristics with salamanders. It was small, only fifteen centimeters in length, and unlike modern legless caecilians, it possessed small legs and had better-developed eyes.

. Our journey cuts south from North America, and we plunge into what is now modern Africa. This is the northeastern portion of the southern continent of Gondwana, and we get a fantastic look at the Early Jurassic environment from the Elliot Formation of South Africa. The Elliot Formation gives us a window into the Late Triassic and Early Jurassic. It’s been divided into the Lower Elliot Formation, which dates back to the Norian-Rhaetian stages of the Late Triassic, and the Upper Elliot Formation, which dates primarily to the Hettangian stage of the Early Jurassic but which also dips into the subsequent Simenurian stage. The Upper Elliot Formation – or UEF for short – is famous for preserving a ‘continental record’ of the Triassic-Jurassic boundary. The UEF’s sandstones are also infamous for containing ‘trace fossils’ of animal trackways, especially those belonging to early ornithischians. Due to the reddish color of the rocks, the Elliot Formation is often called the ‘Red Beds.’ Along with dinosaur fossils, the UEF preserves several crocodylomorphs, fishes and crustaceans, and turtles. At this point in time, southern Africa was a hotspot of volcanic activity that threaded much of southern Africa and Antarctica’s landscape with extensive lava flows. It’s speculated that the UEF gives us a snapshot of an arid floodplain rimmed with dense conifer forests close to the ocean. The fossils preserved were likely inundated by periodic flooding, entombed in sediment, and fossilized for our discovery.

¸ which survived the Triassic-Jurassic Extinction Event. This twenty-foot-long prosauropod was one of the kings of the Late Triassic, but it was being outdone by emergent sauropods such as

(up to fifty feet long, the giant of Early Jurassic South Africa!). As the Jurassic progressed, the prosauropods would be squeezed out, and sauropods would become the dominant – and bigger-than-life – sauropodomorphs of the Mesozoic. The genesis of their rise is documented in Africa, and two more early sauropods from other African locations are known:

was fossilized in northern Africa. Thus even in the Hettangian, early sauropods were dominating various niches. The sauropods of the Elliot Formation likely coexisted due to niche partitioning, in which different genera focused on different kinds of vegetation. Some may have been ‘high-browsers,’ stretching their long necks to feast off trees high off the ground, whilst others were ‘low-browsers,’ sweeping their necks back-and-forth over the ground to devour swathes of ferns and cycad shoots.

|

| a Dracovenator disturbs a flock of heterodontosaurs |

Theropods of the UEF include a variant of

Coelophysis – these small, likely pack-hunting dinosaurs were able to survive the extinction at the end of the Triassic – and a medium-sized carnivore called

Dracovenator. Because our knowledge of this dinosaur comes from partial skull fragments, we can’t precisely narrow down its length, though we assume it’s medium-sized because of similarities to the dilophosaurids (such as

Sinosaurus and

Shuangbaisaurus of China): like them and the later

Dilophosaurus, the back end of its lower jaw features a series of lumps and bumps. Thus paleontologist speculate that it was a medium-sized predator that may have had dual crests on its head.

Dracovenator may have hunted weak or juvenile sauropods, and it may have chased the early ornithischians that bloomed in Early Jurassic South Africa.

|

| a pair of Heterodontosaurus |

Ornithischian origins are murky, but by the Hettangian in South Africa, several species were flocking around in social groups. These early ornithischians generally grew to about five feet in length and could weigh up to twenty pounds. Their bodies were short with flexible tails; their five-fingered forelimbs were long and robust and capable of grasping; their hind limbs were long, slender, and four-toed; their skulls were elongated and narrow and triangular when viewed from the side; and most scientists believe these early ornithischians had long, hollow, feather-like fibers over much of their body. These early ornithischians are known as ‘heterodontosaurs’ because they had ‘heterodont’ (or ‘mismatched’) teeth. While most dinosaurs have a single kind of tooth in their jaws, heterodontosaurs had three: they had small, incisor-like teeth in the upper jaw followed by long, canine-like teeth, and they had chisel-like cheek-teeth behind their fleshy cheeks. Because several different species coexisted – the Hettangian conifer forests and floodplains were home to

Heterodontosaurus,

Abrictosaurus,

Lesothosaurus, and

Pegomastax – it’s been assumed that they, like their sauropod neighbors, practiced niche partitioning.

|

| the Hettangian crocodylomorph Litargosuchus |

The UEF of the Hettangian has revealed two crocodylomorphs and a cynodont (the ancestral heritage of modern mammals).

Sphenosuchus could grow up to five feet in length, making it one of the largest sphenosuchian proto-crocodiles. It was terrestrial and a great runner, and it likely hunted heterodonts or even unwary

Coelophysis. Another sphenosuchian was

Litargosuchus; this proto-croc was smaller than

Sphenosuchus, and it had unusually elongated limbs with its hind limbs slightly longer than its front. Paleontologists believe that

Litargosuchus hunted its prey much like a wolf, though these creatures were probably solitary rather than pack hunters. The Hettangian cynodont

Megazostradon – widely viewed as one of the first mammals – was a small, shrew-like creature that grew between four and four and a half inches long. It was likely nocturnal and fed on insects and small lizards.

|

| the Hettangian cynodont Megazostradon, considered by many to be one of the earliest mammals |

|

| Vieraella, one of the earliest true frogs |

The Fourth Stop: South America. Heading west across Africa, we cross into what is now South America. Though Africa and South America would begin separating via a north-south split in the back-end of the Late Cretaceous, at this point there’s no Atlantic Ocean – not even a seaway – separating the two. If it weren’t for GPS, one wouldn’t know they crossed from one tectonic plate to another. In modern-day Argentina, the small prosauropod

Leonerasaurus prowled conifer forests and fern-swept valleys. Argentina also showcases

Vieraella, the earliest-known true frog. Far to the south of the continent, the five-feet-long theropod

Tachiraptor preyed upon the bipedal, fast-running ornithischian

Laquintasaurus.

|

| a Tachiraptor plunges into a flock of Laquintasaurus in Hettangian Venezuela |

The Sinemurian Stage is the second stage of the Jurassic Period; it follows the Hettangian Stage and is followed in turn by the Pliensbachian Stage. The base of this stage is the appearance of the ammonite genera

Vermiceras and

Metophioceras; the top of the Sinemurian is the emergence of the ammonite species

Bifericeras donovani and the ammonite genus

Apoderoceras. The Sinemurian takes its name from the French town of Semur-en-Auxois, near Dijon. The chalky, limey soil formed from the Jurassic limestone in the region is partly responsible for the character of Sancerre wines. In the Sinemurian oceans, plesiosaurs radiated, and the infamous

Plesiosaurus appears in the fossil record, and a spear-wielding ichthyosaur roamed the seas. One of the earliest new Jurassic pterosaurs,

Dimorphodon, steps onto the scene, and dinosaurs continue to radiate: more sauropods evolve, theropods get larger, and we have the first inklings of the armored thyreophorans that will one day bloom into stegosaurs and ankylosaurs. We look first to the oceans, then to the skies, and then we take a journey across splitting Pangaea to see how terrestrial life is evolving.

|

| a Plesiosaurus on the prowl |

The sixteen-foot-long, fish-eating plesiosaur

Attenborosaurus prowled the shallow seas of prehistoric England. Though this creature ‘walked and talked’ like a proper plesiosaur, scientists classify it as a pliosaur; though it didn’t have the classic ‘pliosaur’ morphology of a short neck and thick head, anatomical features indicate it was more closely related to the later

Pliosaurus than to earlier, more basal plesiosaurs. Another long-necked pliosaur was

Macroplata, which was slightly smaller than its aforementioned contemporary at fifteen feet. It, too, was a fish-eater, using its sharp needle-like teeth to catch prey. Its large shoulder bones imply a powerful forward stroke for fast swimming. Its neck was twice the length of its skull, an anatomical feature more in line with the long-necked ‘proper’ plesiosaurs than with the short-necked pliosaurs. The infamous

Plesiosaurus hunted alongside

Attenborosaurus and

Macroplata during the Sinemurian Period; it would be a staple of northern Laurasian seas up through the Toarcian stage of the Early Jurassic.

Plesiosaurus lends its name to the plesiosaur group, and it’s become associated with the Loch Ness Monster of Scotland. It was much shorter than its contemporaries at only eleven feet (thus ‘Nessy’ would be a behemoth!). The prehistoric

Plesiosaurus had a small, narrow head; a long and slender neck; a broad, turtle-like body; a short tail; and two pairs of large, elongated paddles.

Plesiosaurus likely fed on belemnites (squid-like Mesozoic cephalopods) and fish. Its U-shaped jaw and sharp teeth would’ve acted like a fish trap as it propelled itself by the paddles. It may have used its neck as a rudder when navigating. We know that

Plesiosaurus gave birth to live young in the water like sea snakes, and the young may have lived in estuaries or bays before moving out into the open ocean. Because its long neck may have hindered its pursuit of prey – any slight movement would increase water turbulence – scientists believe it hunted with its neck held directly along the plane of its path. Another theory is that

Plesiosaurus was an ambush hunter, lying in wait and using its elongated neck and big eyes to scan for prey; when prey came close, perhaps its neck darted out, snatching the prey out of the water. Perhaps it was brightly-colored to blend in with prehistoric reefs, nestled among corals as it waited for large fish or cephalopods to wander by.

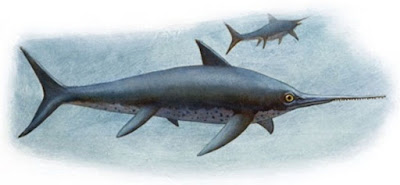

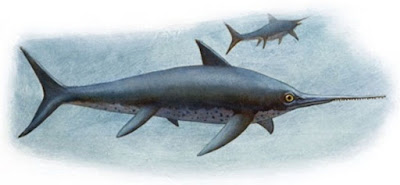

Ichthyosaurus, Temnodontosaurus, and

Leptonectes continued into the Sinemurian, but two new 'spear-headed' ichthyosaurs emerged:

Eurhinosaurus and

Excalibosaurus.

|

| an artistic rendition of the ichthyosaur Excalibosaurus |

|

| a flock of Dimorphodon on a wooded island of modern England |

Though we know pterosaurs survived the Triassic-Jurassic Extinction – they proliferated like kudzu during the Jurassic, after all – our evidence of Early Jurassic pterosaurs is scant. The first well-known pterosaur of the Jurassic is

Dimorphodon, a long-tailed, blunt-headed rhamphorhynchid. It shows up during the Simenurian and survived through the Pliensbachian. This puffin-like pterosaur had a five-foot wingspan and dominated the flurry of wooded islands that was prehistoric England. It stretched 3’3” head-to-tail and its head measured eight inches. The head was large and heavy with a deep, narrow snout. The beak may have been brightly colored in life and used in visual displays; like modern puffins and hornbills, it may have used vibrant colors to ‘stake out’ its territory, to attract mates, or to intimidate rivals. Studies of its hips, legs, and feet indicate that it may have stood upright and balanced on its toes while walking, just like modern birds. This stance makes

Dimorphodon unusual, as most pterosaurs had weak legs that splayed out to the sides.

Dimorphodon’s tail was long and stiff, and its three-fingered hands were strong and curved with sharp claws designed for climbing rocks or trees. The nature of this pterosaur’s eating habits have been hotly debated: was it a fish-eater? an insectivore? or did it hunt terrestrial prey, such as small lizards and early mammals? The current consensus (if we can call it that) is that it was a specialized carnivore, being too large for an insectivorous diet and therefore subsisting off small lizards and mammals (though it may have fished from time-to-time). Given its ecosystem of wooded islands, such a lifestyle wouldn’t be surprising, as islands are often host to smaller organisms than are found on the mainland.

|

| A herd of Barapasaurus in Sinemurian China |

The First Stop: China. As we begin our journey across the Sinemurian landmasses, our first stop is the offshore wooded forests of prehistoric China in what was southern Laurasia. This brooding forest of conifers was interspersed with cycads and tree-ferns, and fossils of turtles, amphibians, and early mammals are abundant. Our knowledge of Sinemurian China comes from the Red Beds of the Lufeng Formation. It was during the Sinemurian that China witnessed its first sauropods, such as

Barapasaurus – which reached up to sixty-six feet in length and, judging by the abundance of fossils, was wildly successful and traveled in herds – and the thirty-foot-long

Kotasaurus, which also traveled in herds. The prosauropods

Yunnanosaurus and

Lufengosaurus, though dwarfed by the emergent sauropods, continued into the Sinemurian.

Bienosaurus, an early but not-well-known thyreophoran – ancestral to the later armored ankylosaurs and stegosaurs – also appeared. The predator theropods didn't experience much evolution, indeed it appears they went through a setback: though the small

Panguraptor and the medium-sized dilophosaurid

Sinosaurus survived into the Sinemurian, the Hettangian

Shuangbaisaurus was nowhere to be seen. The Hettangian crocodylomorphs

Dibothrosuchus and

Phyllodontosuchus are present in addition to several early mammals and kin.

Yunnanodon, whose skulls only reached about an inch and a half in length, were one of the few non-mammalian therapsids to survive the Triassic-Jurassic Extinction Event. Early Chinese mammals of the Sinemurian include

Sinocodon and

Hadrocodium. The latter is impressive, because it has a relatively large brain cavity – like modern mammals – and is one of the first early mammals to have a nearly fully-mammalian middle ear.

|

| the early mammal Hadrocodium of Sinemurian China |

|

| Saltriovenator prowls an Italian beach |

The Second Stop: Europe. Moving north across the supercontinent Laurasia, and nearing Europe, we reach modern Italy to meet the mega-predator of the Sinemurian. Fossils from Italy are rare, and while we don’t know what

Saltriovenator hunted (though we can assume the environment was home to early ornithischians, prosauropods, and emergent sauropods), we know it was more than capable of taking down anything that it came across.

Saltriovenator was the giant of its day, stretching twenty-five feet in length and dwarfing the other predators of its time (theropods its size wouldn’t show up for another twenty-five million years!). Heading further north, we eventually reach western Europe. The ancient waterways cut along Germany and France, and England was a mere collection of low-lying wooded islands. Among these islands was the lightly-built, eleven-foot-long theropod

Sarcosaurus. It’s believed it may have swam between the hundreds of scattered islands in the emergent seaway. We also find the early thyreophoran

Scelidosaurus. This thirteen-foot-long herbivore had a small head with a horny, beak-like front to its mouth. It was quadrupedal, with its rear legs longer and stronger than its forelegs, so that its back sloped up towards the hips (a feature that would be exaggerated with the later stegosaurs). The most notable facet of

Scelidosaurus was the ‘light armor’ it sported on its neck, body, and tail. This armor was comprised of small, pebble-like scales and large bony plates called scutes.

Scelidosaurus’ place in the ‘dinosaur family tree’ is debated: was it ancestral to the later thyreophorans (the armored ankylosaurs and stegosaurs), was it ancestral to one of those two families, or was it an early thyreophoran family all on its own? What

is known is that

Scelidosaurus migrated to northern Laurasia (modern North America), and we follow its journey across the emergent Atlantic Seaway where we run into one of the most famous theropods of all time:

Dilophosaurus.

|

| a family of Scelidosaurus are watched by predators in modern Connecticut |

|

| two Dilophosaurus fight over a Scutellosaurus |

The Third Stop: North America. As we track into northern Laurasia, we reach what is now modern Connecticut. We see a family of

Scelidosaurus walking along the beach as it’s eyed by a pair of small

Coelophysis and a curious juvenile

Dilophosaurus (yes, I basically copied-and-pasted from the image above!). Though

Dilophosaurus is mainly known from Arizona, trackways have been discovered in Connecticut. As we move southwest towards the interior of North America, we may see scattered

Anchisaurus. These prosauropods grew up to thirteen feet in length and were capable of rearing back on their hind legs to reach higher foliage. Though it used to be thought that they were some of the earliest prosauropods, it’s now known they were rather late bloomers. Despite their morphologically basal sauropodomorph anatomy, they developed in tune with the sauropods of southern Laurasia and Gondwana.

As we reach what is now modern Arizona, we come across a litany of rivers and prehistoric Lake Dixie, a massive body of water that stretched from St. George, Utah east to Colorado City, Arizona; and from Cedar City, Utah south to the middle of Arizona. By the Middle Jurassic, this area was being encroached upon from the north by a sandy dune field, but in the Sinemurian it was a lush paradise of vibrant forests, seasonal rainfall, and terrain cut by streams, ponds, rivers, and lakes. It’s no surprise that it was resplendent with a host of creatures calling it home. Here we encounter another early, albeit smaller, thyreophoran,

Scutellosaurus. These five-foot-long, herbivorous early thyreophorans were lightly armored and likely ran around in packs, and they may have been hunted by the larger, twenty-three-foot-long

Dilophosaurus. These predators are famous for their twin swooping head-crests, though there’s no reason to believe they were capable of spitting venom. They may have been pack hunters, and it’s very likely they were actually primarily fish-eaters (they had a lot of adaptations for catching fish, and their frail head-crests would be damaged in fierce combat when taking down larger prey).

Dilophosaurus lived alongside large prosauropods such as

Sarahsaurus, early ornithischian heterodontosaurs, and the lightly-armored

Scutellosaurus and

Scelidosaurus. Smaller theropods such as

Coelophysis hunted in the undergrowth. The environment of Lake Dixie and its environs consisted of freshwater bivalves and snails and various crustaceans. Fossils of hybodont sharks, bony fush, lungfish, salamanders, caecilians, and the early frog

Prosalirus have been discovered, along with the Early Jurassic turtle

Kayentachelys. The remains of numerous lizards and crocodylomorphs, as well as a panoply of early mammals, have been uncovered. The remains of a relatively-unknown pterosaur,

Rhamphinion, have also been studied. It’s safe to say, then, that Lake Dixie was a happening place!

|

| a Dilophosaurus relaxes on the beach at Lake Dixie |

|

| the prosauropod Aardonyx of Sinemurian South Africa |

The Fourth Stop: Africa. As we head south into Gondwana, we come to the volcanically-active region of the Elliot Formation of modern South Africa. During the Early Jurassic, southern Africa was a hotspot of volcanic activity that threaded much of southern Africa and Antarctica with extensive lava flows. It wouldn’t be uncommon to see plumes of acrid volcanic smoke rising distantly above the conifer treetops. The Elliot Formation gives us a snapshot of an arid floodplain rimmed with dense conifer forests close to the ocean. South Africa’s Jurassic menagerie didn’t change much from the Hettangian into the Sinemurian, but there was at least one newcomer, the twenty-foot-long prosauropod

Aardonyx, which had features belonging to both primitive sauropodomorphs and more advanced sauropods.

Aardonyx is considered by many paleontologists to be a ‘snapshot’ of the sort of creature that was transitional between prosauropods and sauropods.

Aardonyx lived alongside the prosauropod

Massospondylus and sauropods such as

Antetonitrus,

Ledumahadi, and

Pulanesaurus. The Hettangian and Sinemurian African sauropods may have diversified and done so well due to a lack of larger theropod predators. The heterodontosaurs of the Hettangian scurried across the forest floor, perhaps hunted by the small theropod

Coelophysis. Crocodylomorphs such as

Litargosuchus and

Orthosuchus may have hunted the heterodontosaurs, as well.

|

| the Antarctic dilophosaurid Cryolophosaurus |

The Fifth Stop: Antarctica. Moving south from Africa, we reach Antarctica. Though nowadays Antarctica is blistery and cold, in the Jurassic Period it was much warmer with a temperate climate. The Hanson Formation has given us glimpses into Antarctica’s Jurassic past: there were late synapsids, herbivorous mammal-like reptiles, and crow-sized pterosaurs that resembled

Dimorphodon. Prosauropod remains, and even fossils belonging to a large sauropod, have been discovered. The most interesting find of all, of course, is that of

Cryolophosaurus, the ‘Elvis Presley’ of the theropods due to backward-sweeping head-crests that look remarkably like that musician’s classic hairdo.

Cryolophosaurus grew up to twenty feet long and may have hunted Antarctic prosauropods. Some scientists believe it was a scavenger or fish-catcher, as its head-crests were fragile and would easily be broken in combat. However, fossilized remains of what appear to be an herbivorous dinosaur’s rib bone was found wedged inside the bones of a

Cryolophosaurus’ throat. Some postulate that this specimen choked on its dinner, though others believe the rib belongs to

Cryolophosaurus and was wedged into its throat postmortem. The purpose of the head-crests were likely for sexual displays or species identification.

|

| The Jurassic Antarctica is not the Antarctica you know! |

No comments:

Post a Comment