Type Species: Diplodocus longus

Classification: Dinosauria – Saurischia – Sauropoda – Gravisauria - Eusauropoda - Neosauropoda - Diplodocoidea – Flagellicaudata – Diplodocidae – Diplodocinae

Time Period: Late Jurassic

Location: United States

Diet: Herbivore

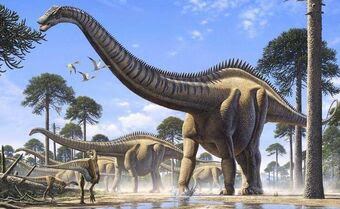

Diplodocus is an infamous dinosaur, a childhood icon, for at least two reasons: for a long time it was thought to be the largest dinosaur, and it’s one of the earliest dinosaurs about which scientists could say a lot. Its remains were first discovered in the late 19th century, and Othniel Charles Marsh studied it immensely during the ‘bone wars.’ He named it Diplodocus longus – meaning ‘long double beam’ – after a pair of long bone growths on the underside of the caudal vertebra (while Marsh thought these features were unique to this sauropod, they’re actually fairly common among sauropods). Diplodocus had the standard sauropod body plan: a long tail, a large body supported by four pillar-like legs, and a long neck. Because its hind legs were longer than its front legs, its body sloped slightly forward. While it could reach up to eighty feet in length, most of that length was accomplished via its long neck and whip-like tail. Its whip-like tail may have served as a defensive weapon or as a tool by which it could ‘crack’ the sound barrier to communicate to other of its kind or ward off predators. Diplodocus may have had keratinous spines running the length of its back; evidence of such spines has been found in later specimens, and they’re known to be present in other closely-related sauropods.

Herds of Diplodocus roamed the low-lying drainage basins that swallowed runoff from the emergent Rocky Mountains in western North America. This lowland environment – which stretched from New Mexico to Canada and is known as the Morrison Formation – was scarred by crisscrossing streams and rivers and was dotted with swamplands, lakes, and floodplains. Diplodocus’ contemporaries included other sauropods such as Apatosaurus, Brachiosaurus, and Camarasaurus; ornithischians like Camptosaurus, Dryosaurus, and Stegosaurus; and carnivorous theropods such as Stokesosaurus and Ornitholestes. The largest predators were Ceratosaurus, Allosaurus, and Torvosaurus. Though a full-grown Diplodocus would’ve likely been nigh invulnerable to these predators, juvenile sauropods or the aged, weak, and sick would’ve been easier prey; some scientists believe that the vulnerability of young sauropods implies that Diplodocus reproduced with an R-strategy of having large nests with lots of young in the hope that even just a few survive into adulthood. If this is the case, it could very well be the case that young sauropods were a prime staple of the predators’ diet in this Late Jurassic ecosystem. Crocodylomorphs such as Hoplosuchus prowled the lowlands, and pterosaurs such as Harpactognathus and Mesadactylus roamed the skies. The aquatic elements of the lowlands were inhabited by ray-finned fishes, frogs, salamanders, and turtles; bivalves and aquatic snails were plentiful. Plant life included green algae, fungi, mosses, horsetails, cycads, ginkgoes, and several kinds of conifers. The nature of the vegetation changed upon ones location in the Morrison Formation: there were river-hugging forests of tree ferns, gallery forests of ferns, and fern savannahs dotted with the occasional conifer. Paleontologists believe Diplodocus stuck mostly to the floodplains and sparsely-wooded areas on the fringes of denser forests that may have been too overgrown for them to navigate; though older interpretations put Diplodocus and its sauropod contemporaries in swamps and lakes, it’s now known they were fully terrestrial creatures.

Diplodocus was likely a low-browser, carrying its long neck above the ground to graze on ferns and cicads; however, some scientists speculate that it could raise its neck up to a forty-five degree angle without putting too much stress on its heart or vertebrae. It may even have been able to ‘rear up’ on its hind legs by using its tail as a tripod. Diplodocus’ peg-like teeth pointed forward, and in adults toothwear is limited to the forward portion of its mouth; this indicates that it was a ‘leaf-stripper’ who fed by closing its mouth around vegetation, capturing the stems of the plant between its teeth, and then pulling back so that as the stems ran through the peg-like teeth, the leaves were stripped off and swallowed. Its snout was longer than those of other sauropods, so that it could fit more plants in its mouth. Interestingly, toothwear of juvenile Diplodocus had teeth in the backs of their mouths, indicating they may have fed by moving their head side-to-side as they stripped stems of leaves. This may have been an easier method of feeding in their young age, a method they rejected as they grew older. As a low-browser, Diplodocus would’ve competed with its contemporary Stegosaurus, but if it could indeed raise its neck higher off the ground, it could feed on plants unavailable to stegosaurs. Some scientists believe Diplodocus may have fed on aquatic plants by standing on the sides of a lake or river and using its long neck to reach out over the water and dip its head beneath the surface to pull up softer water weeds. It likely fed at multiple points during the day and night, as its scleral rings indicate it was cathemeral, active for periods throughout both the day and night; this feeding schedule may have been necessary to keep up with its incredible caloric needs.